My graduate school roommate and I participated in some interesting research at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, MD. This pilot study, a part of the National Children’s Study, was designed to discover what chemicals and biomarkers can be accurately measured in saliva. Many medical tests call for blood or urine samples, and researchers were trying to determine whether saliva could be used instead. Giving blood is an invasive procedure that requires a phlebotomist or nurse, so if hormones or external chemicals can be measured in saliva, the process is much easier and more efficient for both the researcher or health care provider and the participant or patient. In this study, researchers collected saliva, blood, and urine samples and compared analyses to see what data could reliably be gathered from saliva alone.

The researcher had us sign the consent forms in the waiting room of a doctor’s office. Separately, we were called back to give the urine and blood samples, which were fairly standard. We’d go into a bathroom and urinate in a cup for the urine sample. A nurse took a couple vials of our blood, and she did a wonderful job finding my vein and making me feel comfortable. I often become queasy and nauseous when having blood drawn, but this nurse did a wonderful job talking to me and telling me to look away, which helped prevent any nausea.

A side note: Having blood drawn makes some people feel queasy or light-headed, and some people do vomit or pass out. For some, the anxiety inherent in research participation may exacerbate the discomfort. To avoid getting light headed or faint, I’ve learned to look away and also to be the one speaking. A good conversation is nice, but if the nurse is talking the entire time, it makes me anxious. It could be the opposite for you, so keep in mind the strategies that help you remain calm during blood draws.

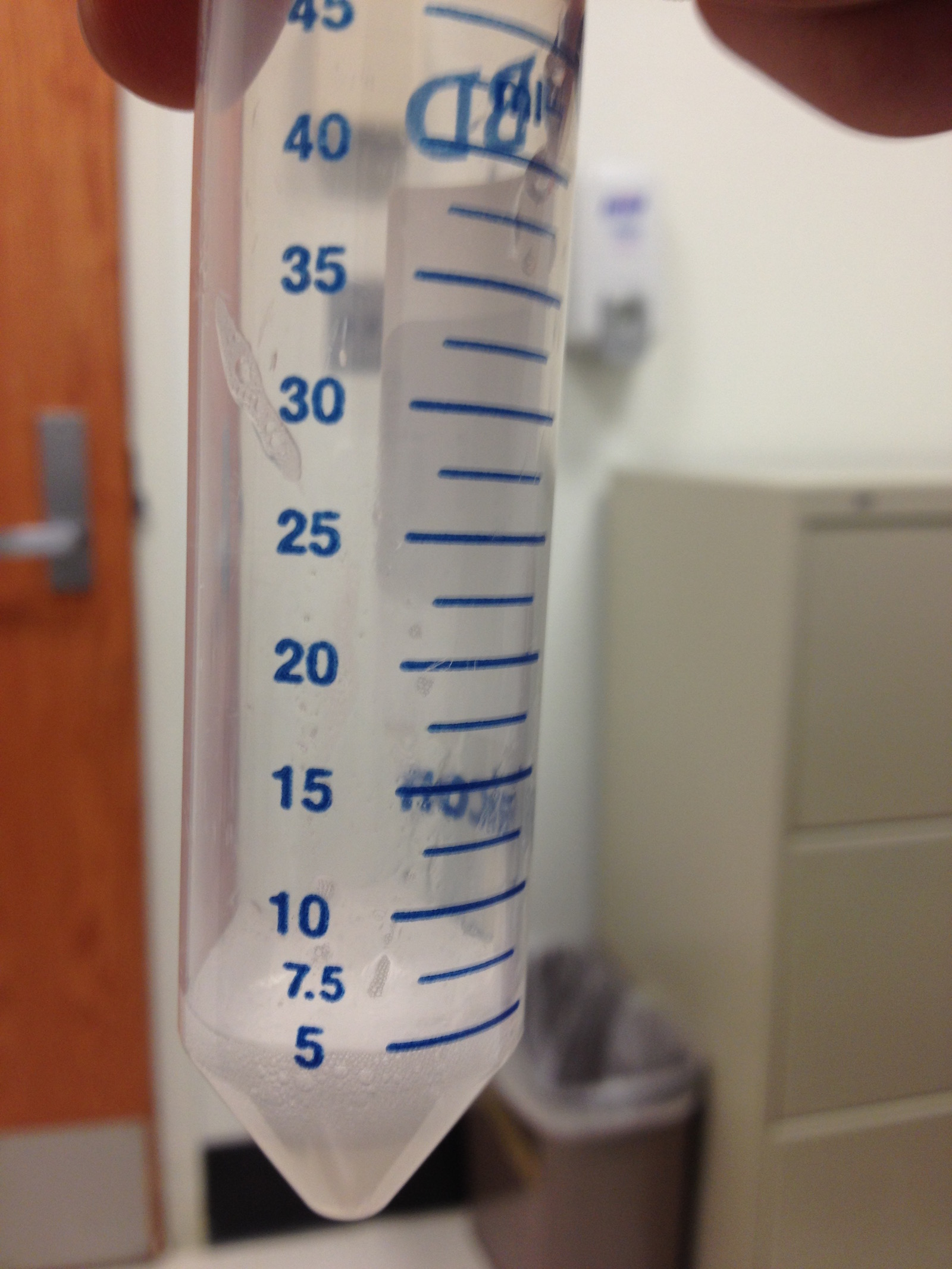

My friend and I sat together as we provided the saliva sample, which seemed to last an eternity. Both of us were given a small plastic tube, pictured above, with a small straw to spit into. This was the point where I received a tip I would go on to use in many a study. It was taking my friend and I quite a while to produce the necessary 50 ml of saliva, so the research coordinator told us to induce a yawn. The yawn caused saliva to fill up the sides of my mouth making it much easier to fill up the tube.

The study took about an hour or so, and we were paid $50 for coming in and providing our specimens. Johns Hopkins made it clear that once we had consented to the study, we no longer owned the specimens or data we had provided to the researchers. In general, as a research subject, you do not profit from any advancements, findings, or products resulting from the research. This is noteworthy because in the 1950s, before established practices were in place for obtaining consent in research, Henrietta Lax’s cells were extracted during a biopsy for cervical cancer without her consent. Her cells, also known as HeLa cells, contributed to countless medical advancements because of their ability to live outside the body, multiply, and grow indefinitely. Although Johns Hopkins never profited directly from the discovery or distribution of HeLa cells, having had the first cells in the world able to live on their own can’t have been bad for their bottom line. The eldest son of Henrietta Lacks continues to lobby for compensation for her estate citing the unauthorized use of her cells leading to decades of medical advances.